Bette Davis: The Fighter Retains the Title of Champion

By Elliott Sirkin

Originally published in The Chicago Tribune, Aug. 31, 1980.

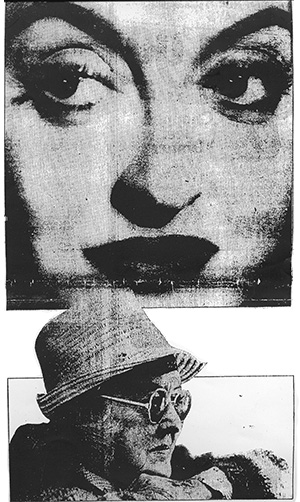

Davis in 1950 (top) and today: “In the arts, you must have your own instincts. I was often afraid of losing an argument because it meant so much to me. But if it involved getting angry, I never harbored it. I got it out. I was never a lady.”

NEW YORK–“So you want to record me? Oh, all right, I’ll go along. But tell me. What do you do with the tapes when you’re through with them? Sell them at a high price?”

Bette Davis’ eyes flash. Striding around her hotel suite on 3-inch-high, disco style heels, she looks pretty much the way she should — big red bull’s-eye mouth, ash-blond pageboy, lapis-lazuli-colored eyeshadow. Dressed in a red blouse and black skirt, she appears feminine, elegant, extravagant, and regal.

She settles into a little cane armchair.

“It always kind of amuses me,” she says. “I still get a huge amount of fan mail. Lots of little children write me. They’ve seen movies of mine on television — that’s really the continuing career — and they send me drawings and mash notes. So cute! I always answer anything that comes from the little ones.”

In 1931, Davis was a little contract ingenue from suburban Boston making her debut in movies. The film was “Bad Sister,” which featured a young Humphrey Bogart; and because her colleagues thought she was pitiful and helpless, they called her “the little brown wren.”

The next five decades changed all that. The wren spread her wings. And Bette Davis became, well, Bette Davis.

Her newest movie is Disney’s “The Watcher in the Woods,” but the best new Davis films have been made for television. Last year she won an Emmy for “Strangers,” beating out Katharine Hepburn, Mary Tyler Moore, and Carol Burnett. Last March, an audience of 25 million saw her as the slum widow in “White Mama.”

“You know,” she says, “when I was at Warner Bros., people believed movies were somehow inferior to plays.” Davis smiles: nitroglycerin on velvet. “Now we’re getting the same snobbery all over, only now it’s theatrical films that are supposed to be superior to the ones on television. It drives me mad, just mad to be on the set of a TV film and hear somebody on the crew shrug at a blunder and say, ‘Oh, what does it matter? It’s only going to be on the box.’ It does matter. You must care.

“We made ‘White Mama’ in a month. One month. It can be done.” Davis whacks the chair’s arm. “It can be done if you are on time”—a whack—“if you know your lines”—another whack—“and if you do not spend 100 hours fussing with your hair and all the other nonsense that is permitted to go on today.”

Davis is tiny, barely 5 feet 3 inches, and she is 72 years old. But she radiates the energy of a prizefighter.

In 1936, when Warners wanted her to play a woman lumberjack, she broke her contract, sailed to England, fought the studio in court, and lost. But she fought.

For 50 years, she has fought. Fought for parts, fought for directors, fought for interpretation, fought for straightforward advertising (“I could never stand to deceive the public”), even fought to have a single line changed. Yet she doesn’t like to call it “fighting.”

It presents an image of people screaming and hitting one another. What I had was discussions about my beliefs. I was not always right, I did not always win, but I always stated my case.

“In the arts, you must contribute, you must have your own instincts. You will never get there if you don’t. I was often terribly afraid of losing an argument, because it meant so much to me. But if it involved getting angry, I never harbored it. I got it out. As for that whole business about showing your temper meant you weren’t a lady, well, I was never a lady.” She laughs heartily and huskily.

Those are the Davis mottoes, repeated with intensity: “You must contribute” and “Everything matters.” In 50 years and 87 movies, “I was tempted to give in and let things slide. Nowadays I am tempted to very often, but,” she says, stretching one syllable into five, “I ca-a-a-n-n-n’t.

“In the ’30s, when my career started, there would have been no chance. I was so dedicated to really making it. But, yes, of course now it would be easier to just say, ‘Oh, pooh, why bother?’ But you just must not, not, not allow yourself to. You know the marvelous saying from Robert Burns?”

Now Davis half-rises, one arm stretched upward, and recites: “I have fought all my life; why not one fight more?”

For a moment, the hotel suite becomes an amphitheater, echoing with her voice. But Davis is not a stage actress. “Why do I prefer the screen? I have always believed in realism. And I always thought the screen offered you a great chance to look and behave as much like the character as you could possibly want to. That was really the whole basis of my belief in my career. Not caring how I looked as long as I looked like the person.”

As Mildred, the waitress-prostitute in “Of Human Bondage,” she had her breakthrough role. Emaciated and bug-eyed, she tormented an oversensitive Leslie Howard before dying — very realistically—of tuberculosis. That was 1934.

“Oh,” Davis says, “what a good and lucky break I had there. One of the greatest parts written for a human being in the history of the world. Not one of the leading ladies of the day would go near Mildred. And that was because she was really the first mean, unattractive heroine that had been on the screen.

“Though personally, I never did like the movie.”

When asked why, Davis stares blankly.

“I don’t know. But then, I never cared much for myself on the screen. Ever. Many, many actors are like that.”

In 1938 Davis appeared in “Jezebel,” the story of a headstrong New Orleans woman destroyed for her own willfulness. Critic Pauline Kael would later call Davis’ performance “a full-scale demonstration of the talents of a star who could also act.”

“That was my first movie directed by William Wyler,” Davis says, “and let me tell you, he was the greatest director the town of Hollywood ever saw—or will see again. Willie knew exactly what he wanted. Told me he’d put a chain around my neck if I didn’t talk slower, and he always used to say he didn’t run an acting school.

Davis: At 72, a Fighter

“Now the trend is for actors to want to direct. I would never want to. No actor should; it’s a whole different profession. You’ve got to know the camera; you’ve got to know a mil-l-l-l-lion things. You can have the greatest script in the world and a stupid director, and there will be nothing you can do but fight through it and half-direct yourself.”

Six weeks into “Jezebel,” when the studio wanted Wyler replaced by a faster director (“They really could be very stupid in some areas”), Davis agreed to work 15-hour days to accelerate the filming. Her perseverance paid off; “Jezebel” brought her a second Oscar. (She had won in 1935 for “Dangerous.”)

But the critical consensus is that “Jezebel” was the first in the pantheon of great Davis roles — the roles where her fierce glow burned through her scenes. In “Dark Victory” (1939), she played Judith Traherne, a rich girl bravely accepting death after some bravura scenes of nihilistic fury. The film was made in five weeks.

“I mean,” she says, “these schedules today are alarming and absurd. ‘The Shining’ took a year and a half to shoot and a year and a half to edit, and the actors lost their minds. I would be so bored. No, I mean it. Really, I would go berserk. There’s no character you could live with that long. Gable told everyone he nearly went mad from a year of ‘Gone With the Wind.’ I would just lose my mind.

“One part I could have stayed with longer was Queen Elizabeth I. I’ve always been sure that I’m her reincarnation, absolutely positive.”

Her face painted chalk white and encircled in platter-like ruffs, Davis made “The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex” when she was 30, half Elizabeth’s age.

Talking about the characters she has played on the screen, Davis is often morally severe, a possible legacy from her New England childhood.

When asked if she believes the recent accusations that her Lord Essex, Errol Flynn, was a Nazi spy, she replies, “I could hardly imagine it.”

This year — perhaps in recognition of her 50-year contribution to screen acting—Davis was asked to present the Oscar for best achievement in sound. She declined the honor. Mention her 1940 term as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and she practically explodes.

“Unbelievably enough, they gave me that job just when I was getting a reputation for being frank and outspoken, thinking I would be a patsy. But I took my privileges as president very seriously. That was when we were entering World War II, and I had a brilliant, brilliant idea. I wanted to charge $50 for a ticket to the Oscars, with everything going to British war relief.

“That would have meant changing the ceremony from a hotel dinner to something more theatrical. Well, when I made that suggestion, there was an uproar you would not have believed. The academy going into a theater? Did I want to sully the dignity of the academy? Well, when you see what’s happened to the awards today, you know you have to croak.”

Most Davis smiles are warm. This one is like a block of dry ice. “Now, the lovely part of the story is that when I sent in my resignation, (producer) Darryl Zanuck said, ‘You’ll never work in this town again.’ I told him as long as I have a Warners contract, I think I’ll be all right.”

In 1942, Paul Henreid in “Now, Voyager” lit two cigarets and handed Davis hers as if it were a talisman. Of course the cigaret, rising from her fist, surrounding her in a halo of smoke, is Davis’ insignia. She even tried to stop smoking “once, many years ago, but I was so mean and terrible, my friends begged me to go back.”

In the ’40s, she played an unnerving number of evil and neurotic women. A catchy advertising slogan at the time captured them perfectly: “No one’s good like Bette when she’s bad.” Married to “Mr. Skeffington,” she humiliated Claude Rains and ignored their child. Directed by Wyler in “The Little Foxes,” she was stone-faced while husband Herbert Marshall died of heart failure. “The Little Foxes” made her the highest-paid star in Hollywood. The year it was made, only MGM chief L.B. Mayer had a higher salary.

And Still a Champion

Bette Davis in the 1941 film “The Little Foxes”: The year it was made, only MGM chief L.B. Mayer had a higher salary in Hollywood.

In August of 1949, after a dispute over her future roles, she left Warner Bros.

“What do you mean, can I remember my last day at Warners?” The question is obviously not a good one. For a moment, Davis looks like a closeup of herself in “The Little Foxes.” “Do you think I’m senile? I remember practically every day at Warners. Everybody knew everybody, everybody worked together for years. That was true of all the studios. We were like a family.”

Davis once described a fellow member of the “family” as “a nice, pleasant little fellow.”

“Oh, you mean Reagan! Well, he’s still a nice, pleasant little fellow. You want me to say more? I’m certainly not going to vote for him. Let’s put it that way, shall we?” A gale of laughter follows.

What is her signature role? No question: Margo Channing, the actress-heroine of 1950’s “All About Eve.” No one forgets Margo’s drop-dead chic, or the way she swung her pelvis and roared, “Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.” As Margo, Davis was plundered by Eve, the little sneak who pretended to be her greatest fan.

“That film had the greatest script about theater people that will ever be written, and everybody in it was just great. It was just one of the great films. How we all loved making it! Anne Baxter as Eve was ter-r-r-r-rific! Thelma Ritter as my maid—adorable! I really couldn’t stand it when Thelma died.

“Now, I’m not often proud of a performance,” Davis continues, “but I’m very proud of Ma Hurley in ‘The Catered Affair.’ I loved her.” In the 1956 film, Davis played a beaten Bronx housewife, obsessed with giving her daughter an elegant wedding.

“Too bad it’s such an unsung film. MGM just dumped it here. But in England, it was a great, great triumph. Ma was an enormous departure for me.”

Heavy on ethnic pathos, the role of Ma Hurley really was an enormous departure. But “The Catered Affair” was the last worthy vehicle Davis would have for years. In the 1960s, there were few roles for actresses her age, and in films like “The Nanny” and “The Anniversary,” she had to parody herself as a demented, criminal shrew. In “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” she fed costar Joan Crawford dead parakeets and rats.

The film was the surprise hit of 1961. But Davis was never a Crawford admirer. On the set, she never saw the Crawford described in “Mommie Dearest.”

“I never really knew Joan. We did ‘Baby Jane’ in three weeks. But I read that book in a state of shock, and it didn’t make me feel the least bit sorry for Joan. She was clearly not a disciplined personality, and her problem was obvious. Drink.” The last words are carefully measured and emphatic.

“From my standpoint, at least, people have misjudged ‘Mommie Dearest.’ All they can say now is, ‘How dare that girl write such things about her famous mother?’ Well, she did and it was her business and she had every right to. It’s the story of an adopted child who wanted her mother’s love so much that she tried every means known to man to get it. Tried and failed.”

As for her own private life, Davis is the mother of three, and has had four husbands: Harmon Nelson, Arthur Farnsworth, William Sherry, and her “All About Eve” costar Gary Merrill. In her memoirs, “The Lonely Life,” published 17 years ago, she minced few words about her offscreen life. In the last chapter, she wrote, “I know that my marriages—all of them—were a farce.” She has nothing to add to that, except that, “as of six months ago, I have a new ruling when it comes to discussing marriage. Pitch it! I haven’t been married now for 20 years, it didn’t work, and I have nothing more to say.”

At that point, the likelihood of a parallel between “The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex” and the private life of Bette Davis is brought up. In the movie, the conflict arose over a man’s resentment of a woman’s power.

Davis pauses and thinks. Then, as the words tumble out slowly, she and Elizabeth almost seem to merge.

“In my case, it was the resentment of my fame, not my power. Resentment of fame. That makes professional marriages very difficult, especially if the fame is on the woman’s side. Yes, yes. I guess if you could boil my marriages down to one thing, it would be that item.”

Then perhaps “The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex” could have been titled “The Lonely Life”?

Davis laughs.

“Oh that’s lovely, just lovely. But my book wasn’t ‘A Lonely Life’; it was ‘The Lonely Life’ and I think that applies to all of us in the arts. We do mad, peculiar work, and we are lonely, driven people. We don’t have millions of friends who understand what our lives are all about.

“I once did a fan magazine article called ‘I Am Not the Girl Next Door.’ Well, I never got such a bunch of letter. Who did I think I was? What was I saying? But that is the story of my life.”

Two hours have gone by, and in an almost Cubist effect, chips of all her great characters have flown off Davis. Margo’s verve, Elizabeth’s wisdom, Ma Hurley’s sadness, Judith Traherne’s bravery, Jezebel’s rage. She is a mosaic and a rainbow of all the heroines “the little brown wren” had hidden inside.

In 1925, actress Eva La Gallienne rejected Davis from her drama school. She didn’t find her “serious enough” to become an actress.

“Do I bear her a grudge?” Davis looks nonplussed. “Oh, no, I don’t bear grudges. In this case, how could I? Miss Le Gallienne was wron-n-n-g-g-g.

“I made it alone.”

Bette Davis, Actress (from Radcliffe Institute’s Notable American Women)

By Elliott Sirkin

Originally published in Notable American Women (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004) pp.152-54.

DAVIS, Bette. April 5, 1908—October 6, 1989, Actress.

At her best, Bette Davis put complicated, conflicted women on the screen at a time when most screen characters were still melodramatic simplifications. A small (five foot three) blue-eyed blonde, she was unfazed by the cant of her era that considered screen acting inferior to acting on the stage. An actress first and a star second—and in no way a conventional beauty—she invented a jagged, sincere, many-sided style of film acting that continues to reverberate through the generations.

Born Ruth Elizabeth Davis in Lowell, Massachusetts, she was the elder of two daughters of Harlow Morrell Davis, a patent lawyer from a Yankee family of long standing, and Ruth Favor, a homemaker of French Huguenot descent. The couple, incompatible almost from the start, divorced when Betty was ten. As a result, she and her younger sister, Barbara, were educated in a patchwork of public and private schools in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts—wherever Ruth Davis could find work as a professional photographer or housemother. Popular and active as child, Betty changed the spelling of her name in imitation of Balzac’s La Cousine Bette and finally graduated from Cushing Academy, a boarding school in Ashburnham, Massachusetts, in 1926.

By 1927, a nineteen-year-old Bette Davis was attending the John Murray Anderson-Robert Milton School of Theatre and Dance in New York. Although she starred in term plays and studied with Martha Graham, Davis was temperamentally restless and eager to earn a living. She left school before her first year was over, rushing headlong into professional engagements on and off Broadway, on tour, and with numerous stock companies, among them George Cukor’s repertory theater in Rochester, New York.

After opening on Broadway in Solid South (1930), she received her first offer from a Hollywood film studio. With a few exceptions—most notably Cabin in the Cotton (1932)—Davis’s first years in Hollywood produced nothing extraordinary. Then, in 1934, after a long campaign, she convinced Warners to loan her to RKO to play the sociopathic cockney Mildred Rogers in their adaptation of Of Human Bondage, and got her first star-making notices. The next year she won an Oscar for Best Actress for Dangerous (1935), in which she played an alcoholic actress patterned on the Broadway legend Jeanne Eagels.

In 1936, Warners had to sue to prevent her from violating her contract and making a film in England for the Italian producer Ludovico Toeplitz. When she returned to Warners, however, she was treated generously, starring next in Jezebel (1938), a finely wrought study of the anger and ambivalence of a southern belle. The performance—fueled by an adulterous affair with the film’s director, William Wyler—brought her a second Oscar, as best actress of 1938. The next year she played the role that she sometimes referred to as her favorite, Judith Traherne, the mortally ill heroine of Dark Victory (1939). After Dark Victory, Bette Davis starred in an unbroken string of sixteen box-office successes, playing everything from genteel novelists to murderous housewives to self-hateful spinsters to a sexagenarian Queen Elizabeth I. Her most memorable films from this remarkably productive period included The Old Maid (1939), The Little Foxes (1941), Now, Voyager (1942), Watch on the Rhine (1943), and The Corn Is Green (1945).

In 1932 she had married her high school sweetheart, Harmon Nelson, a freelance musician. But the marriage was as rocky as her parents’, and in 1938 Nelson found her with Howard Hughes and divorced her. Davis married again in 1940, to New England hotelier Arthur Farnsworth; he died in 1943 from a mysterious compound skull fracture. The war years were Bette Davis’s prime, and not only on screen. In 1941 she became the first woman president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, quitting when she realized she was little more than a figurehead. In 1942, with John Garfield, she co-founded the Hollywood Canteen. Totally committed to her role as the organization’s president, she danced, ate, and clowned almost nightly with the servicemen passing through Los Angeles.

Yet after the war, Davis’s career began to sink, with terrible films such as Beyond the Forest (1949), more parodies of Davis vehicles than the real thing. Released from her Warners contract, she freelanced. At forty-two, she seriously believed her career was over, until her performance in All about Eve (1950), where she played, not coincidentally, an explosive theatrical prima donna who was terrified of aging. For her performance as Margo Channing, New York Film Critics named her the year’s best actress.

Having divorced William Grant Sherry, a painter whom she had married in 1945, in 1950 she married All about Eve’s leading man, Gary Merrill. With Sherry, Davis had had one child, a daughter, Barbara Davis Sherry, nicknamed B.D. (1947). With Merrill, she adopted two others, Margot Mosher Merrill (1951), who was brain damaged, and Michael Woodman Merrill (1952). The Merrills lived in Cape Elizabeth, Maine.

By 1960, while Davis and Merrill were touring together in The World of Carl Sandburg, it became clear that that marriage was finished, and they divorced. In her best-selling autobiography, The Lonely Life (1962), she took responsibility for her failed marriages, but wondered if somewhere there wasn’t a man who could tame her. In the book’s coda, a long, agonized meditation on women and freedom, Davis ruefully compared herself to her character Julie Marsden in Jezebel and confessed that in her relationships with men, she had always had to remain in charge, but inevitably lost respect for them when they allowed her to.

In 1962, no longer a box-office name, she took a role in an offbeat, low-budget psychological thriller, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, poignantly playing a homicidally demented middle-aged former child star alongside co-star Joan Crawford. The film was a megahit, bringing Davis her tenth, and final, Oscar nomination. The downside of this comeback was that for years afterward, she was offered almost nothing but lurid films about decrepit gorgons, and in films like The Nanny (1965) became something of a laughingstock.

In the new era of made-for-TV films and mini-series, however, worthwhile roles came to her again, including a part as a pathetic recluse in Strangers (1979), for which she won a best-actress Emmy. In 1977, the American Film Institute bestowed on her its Life Achievement Award; she was the first woman to receive it. Almost more prominent than she had been at her zenith, she now found herself hailed by a new generation of film critics who were seeing her classic films for the first time, while new stars—most notably Jane Fonda—praised her warmly as an influence and a role model.

In 1983, she suffered breast cancer and a stroke. Despite permanent damage to her speech and gait, she continued making films. In 1985, Davis was shattered when her daughter, B.D. Hyman, published a contemptuous family memoir, My Mother’s Keeper. She feebly tried to respond in her own book, This ’n That (1987). Then, looking dismayingly frail, she played a scrappy octogenarian opposite Lillian Gish in The Whales of August (1987), a sensitive study of old age.

Bette Davis died of cancer in Paris in 1989, having gone to Europe to accept an award at a Spanish film festival. Eighty-one at the time of her death, she left behind on film a brilliant constellation of contrasting and vibrant figures, the legacy of sixty years of hard work and dedication to what she liked to call total realism on the screen.

Bibliography: A collection of Davis’s personal papers, photographs, scripts, and scrapbooks is located at the Twentieth Century Archives, Boston University. An outstanding source of information is Randal] Riese, All about Bette (1993), which contains a filmography and a complete list of Davis’s awards. Biographies include Shaun Considine, Bette and Joan: The Divine Feud (1989); Charles Higham, Bette: The Life of Bette Davis (1981); Barbara Learning, Bette Davis: A Biography (1992); and James Spada, More than a Woman (1993). Davis wrote two autobiographies, The Lonely Life (1962), with Sanford Dody, and This ’n That (1987), with Michael Herskowitz. Memoirs wholly or in part about Bette Davis include Sanford Dody, Giving Up the Ghost (1980); Elizabeth Fuller, Me and Jezebel: When Bette Davis Came for Dinner—and Stayed (1992); Vincent Sherman, Studio Affairs (1996); and Whitney Stine, I’d Love to Kiss You… (1990). See also Time, March 28, 1938, pp. 33-34; Current Biography (1941, 1953); and Janet Flanner, “Cotton-Dress Girl,” New Yorker, February 20,1943, pp. 19-24. Some information in this essay is taken from a taped interview with Bette Davis by Elliott Sirkin on April 25, 1980. Obituaries appeared in the Los Angeles Times and New York Times on October 8, 1989, and in Variety on October 9, 1989.

Elliott L. Sirkin