Bobby Short: Singing the Praises of Ethel Waters

The late singer, a star of radio, film and TV who paved the way for other black performers, is remembered tonight in ‘Stormy Weather,’ a Kool Jazz Festival tribute coproduced by pianist Bobby Short.

Bettman Archive Photo

Movie Star News Photo

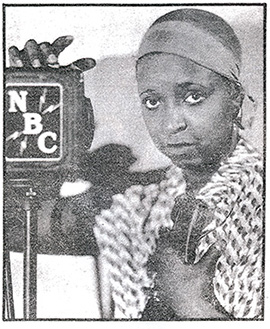

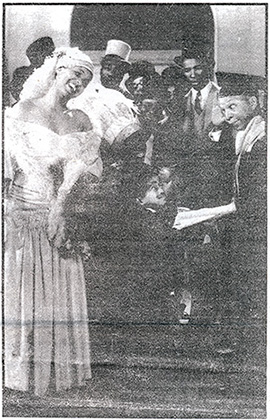

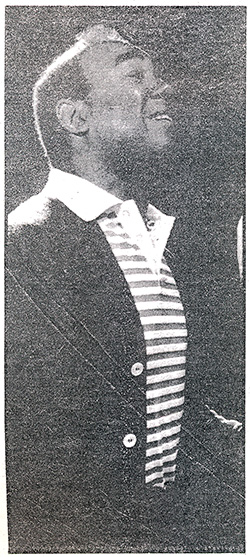

Bobby Short, below left, rehearsing for tonight’s salute to Ethel Waters, notes that she was the first black singer with her own radio show, above, in the Twenties. She went on to films such as ‘Rufus Jones for President’ in 1933 with a young Sammy Davis Jr. and Clarence Muse, right.

By Elliot Sirkin

Originally published in Newsday, June 27, 1985.

Newsday / Jim Peppler

Bobby Short, by general admission one of the most elegant men in New York and certainly its best known singing pianist, sounded a little grouchy in his duplex in the West 50s. Bad even by the unpleasant standard New Yorkers have learned to live with, the noise from the street—construction sounds and taxi horns—was hard for him to compete with, and though he looked cool enough in a starched white Oxford shirt and moderately tapered blue jeans, he sounded hoarse.

The hotel strike had been keeping him out of his regular nightly job at the Carlyle Hotel’s Cafe Carlyle. “I can’t tell you what it’s like for a man like me,” he said, “who’s been working his whole life, not to work. I’ve even found myself getting negative with my secretary. And I can’t cross that picket line. I’m in the musician’s union, baby.”

When questioned, he admitted he exaggerated: Actually he has had a lot of work in the last few weeks, though maybe not the very heavy load customary for the former child star who began performing professionally close to 50 years ago.

Tonight, at Carnegie Hall, he emcees the Kool Jazz Festival’s “Stormy Weather—A Salute to Ethel Waters,” a tribute to the first black singer to successfully cross the color line in American popular music. Short is also, with the Jazz Festival’s George Wein, the evening’s coproducer. “It’s not going to be much of a money-maker for me. But I’ve loved doing it.”

Ethel Waters is probably best remembered, at least by people under 40, not for her music, of which there was a great deal, but for playing a comical domestic on the popular ’50s TV series “Beulah.” In the ’70s, when she was broke and forgotten, with total sincerity she became involved with the Billy Graham crusade, singing old Negro spirituals at prayer rallies. “It’s a sad thing that most people today don’t know about—Ethel Waters,” Short said. “She became a star in the Twenties, and she died just a few years ago [in 1977].”

Her early life and career are what were really extraordinary, and the story is well told in her best-selling 1950 autobiography, “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” (still one of the only show-business autobiographies ever serialized in The Atlantic). Conceived as the result of her 12-year-old mother’s being raped at knifepoint, Ethel Waters grew up in the filthy shanties of Chester, Pa., running prostitutes’ errands and heading a ring of pickpockets. At 15, she quit cleaning hotel rooms and started her career in black vaudeville, where, with a high, angelic purity that is still vivid and electrifying on the reissues of her records that Bobby Short collects, she sang sweet and dirty blues.

By 1930, in spite of being black, she was one of the country’s top singers, introducing such hits as “Takin’ a Chance on Love,” “Stormy Weather,” “Heat Wave,” and the classic “Supper Time.” (Now forgotten, except in a campy Barbara Streisand version, “Supper Time” was the monologue of a young black mother in the South, just having learned of her husband’s lynching.)

“One of the things that was so marvelous about Ethel Waters,” Short said (his “marvelous” being the old-fashioned cafe-society MAHvelous) “was that she influenced so many people. Her respect for her songs and her eloquent dramatic sense and her impeccable diction—that’s something she shared with Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey—and her enormous, enormous natural elegance, all of that influenced people. My God, without her there could have been no Ella Fitzgerald. Ella would be the first one to tell you that. And how Ethel Waters influenced me. She was very, very sly, knew just how to slip in to a song.”

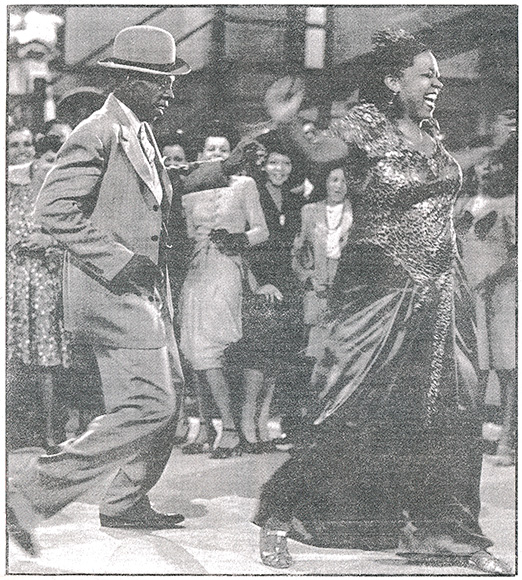

Movie Star News Photo

Waters with John Sublett in ‘Cabin in the Sky,’ a 1943 film, and below, with Rosey Grier in a 1970 TV show.

By this time, Short had kicked off his elegant, multicolored Italian loafers and was sitting flopped backward on the black leather couch, his legs spread apart gracefully. “Ethel Waters opened so many doors. She was the first black singer to have her own radio show, the first star in a racially integrated Broadway show [Irving Berlin’s ultra-chic “As Thousands Cheer” of 1933], the first to have pop songs written expressly for her. Before she came, black singers recorded black blues for all-black labels, and that was it, honey.”

AP Photo

In spite of his obviously deep personal feelings, Bobby Short met the subject of this evening’s salute only once, in 1937, when he was a teenage singer and she was headlining in vaudeville. He remembers having pushed his way in for an appointment, accompanied by his agents, and playing the piano for her.

“She was very maternal,” he recalled. “I think the sight of little Bobby Short brought that out. I also think she had an enormous interest in me as a young black performer. She just laid out my agents, who were white, asking them, ‘What are you going to do for this young man? Where is he booked next week?’ She was a very overpowering lady and very, very tough. Her conduct, her demeanor, her language, they could all be terrible. There are thousands of stories about her bad behavior on the set of ‘Cabin in the Sky,’ the movie she made with Lena Horne.

“But you have to realize that so many ladies in show business get tough. In Ethel Waters’ case, her trouble wasn’t just that she got off to such a bad start, but that she was also screwed…when she started in black vaudeville. And I can identify with that, believe me, I can sympathize. I had to live with some of the same things myself.”

Short’s tones are normally mellow, the intimate, seductive quiet of his delivery being the major source of his cachet as a vocalist. But re-creating the indignities suffered by Ethel Waters, his voice became more and more harsh, until he was almost shouting, and not simply to make himself heard over the racket from the street.

“Forget about getting off the…Jim Crow train and trying to get a taxi cab to take you to some rooming house, or some ramshackle hotel. Think about arriving at the theater, the dirty old broken down theater, where it was dog eat dog. I’m sure at times it was a lot of fun”—Short said “fun” very scornfully. “If it weren’t for that sense of fun, you couldn’t have gotten through half that putrid stuff. But a singer like Ethel Waters had to go out there, doing five shows a day, with no microphones, and make herself heard in the second balcony.

“Plus—I know she wrote this in her book—there were always people running up and down the aisles carrying on and eating pork-chop sandwiches and yelling and screaming while she was trying to perform. Of course, you can always be both the observer and the performer at the same time, but don’t you think she wanted to hear herself sing?” (This last remark was especially poignant and striking; it is not any secret that Bobby Short is often frustrated by the behavior of some of the expensive clientele at the Cafe Carlyle who talk, smoke and generally behave as if they were in the own living rooms.)

“And I’ll tell you something else, something else I respect about Waters, more and more. I respect the fact that one day, performers like her just say, ‘To hell with it, I’m tired, I quit.’ Another burden of hers was that she was expected, as a black artist who had made it, to somehow support her race. People were critical of her for not ‘upgrading’ the image of the Negro, for coming out and singing ‘Supper Time’ with a bandana around her head. But that’s all she got asked to do. I don’t see what more people could have wanted from her. She was an actress. A singer! She wasn’t royal blood.

And yet, in her own way, Ethel Waters did make her statement. In her own, very subtle way, she broke through and said something subversive. I remember how in one of her films, she had a song called ‘Darkies Don’t Dream.’ The title makes you laugh, doesn’t it? Doesn’t it? That song has a very cynical lyric, something about how darkies never dream, they just sing all day. But what vitriol, what contempt Waters showed when she sang it, how she mocked the thought behind it. So, even within these boundaries, there she was, trying to present this woman in the bandana as having aspirations toward something better.”

Short seems like a man who is constitutionally incapable of remaining angry about something for very long. He turned to the subject of tonight’s concert again.

“I’m so proud of the cast we have. Hey, we’ve got Neil Carter, who just closed in Ma Rainey’s ‘Black Bottom,’ to sing ‘Heat Wave,’ and Theresa Merritt will do ‘Supper Time.’ We’re going to have film clips, too, like the one where she does the jitterbug in ‘Cabin in the Sky.’ And then we’re going to have little Bobby Short, who met Ethel Waters in 1937, when he was still a kid. He’s going to be the host and play the piano and sing ‘Dinah.’

“You know,” Bobby Short said, “ ‘Dinah’ was the song that made Ethel Waters a star.”